Veterinary Anesthesia and Sedation 101

One of the most common worries that I discuss with clients is their concern for their pet who requires a general anesthesia. In this post, I will be discussing the difference between sedation and general anesthesia, and indications for each. I want pet owners to better understand the true risk/benefit of these procedures and all of the measures that a veterinary team takes to ensure the highest degree of safety for their patients.

I have noticed a common perception among clients that sedation is safer than general anesthesia. In reality, the sedative drugs (and doses required for heavy sedation) can have more profound depressive respiratory and cardiovascular side effects than those drugs used for general anesthesia. Animals that have underlying health concerns (eg. heart disease, respiratory pathology, kidney or liver dysfunction) can have higher rates of complications during heavy sedations. Secondly, monitoring a sedated patient is often not as comprehensive as during a general anesthesia. Thirdly, the patient’s airway is generally not secured under sedation compared to a fully anesthetized patient.

WHY THEN, DO WE SEDATE ANIMALS?

Sedation is often preferred for young, healthy pets that may require quick diagnostics (radiographs, ultrasound, CT scans, skin biopsies) or treatments (wound repair, placement of casts or bandage changes). The degree of sedation is chosen based on the expected duration and invasiveness of the procedure, as well as patient temperament. Sedation can also be preferred due to the lower cost to the client.

Sedative and opioid medications

An anesthetic machine delivers a combination of pure oxygen and an inhaled anesthetic into the patient

General anesthesia is preferred to safely perform longer and more invasive procedures. General anesthesia provides amnesia, analgesia (pain control) and muscle relaxation for the patient. Current anesthesia-related mortality rates are very low (0.05% dogs, 0.11% cats) for healthy pets. The anesthesia related mortality rates increase as the patient’s health status decreases. Each patient is given an ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologist) rating, which is a system for rating a patient’s anesthetic risk. This helps veterinarians to predict the risk of anesthetic morbidity and mortality and to create the safest individualized anesthetic plan.

ASA chart

In addition to a thorough pre-anesthetic history and exam, many older patients require additional diagnostic tests such as blood work, urinalysis, and sometimes, diagnostic imaging. Pre-anesthetic bloodwork and urinalysis are laboratory tests that allow us to detect otherwise hidden changes in organ function, red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet parameters. Pre-anesthetic chest radiographs and sometimes heart ultrasounds can be required to diagnose and treat heart/respiratory diseases. An abnormality in any of these pre-operative tests warrants further consideration of ways to stabilize (and therefore to improve the ASA status of) the patient before anesthesia, and which anesthetic drugs to avoid.

In-house blood analysers

WHAT IS A GENERAL ANESTHESIA PROCEDURE?

There are three main steps to a general anesthesia:

1. Premedication. This a combination of a sedative and an opioid pain medication that is injected into the patient. Combining these synergistic drugs in a premedication allows us to use lower doses of each drug with a greater effect and therefore less negative side effects on the patient. The sedative allows for reduced patient anxiety/stress and facilitates patient handling to place an intravenous catheter. The opioid provides analgesia (pain control) before the pain stimulus (surgical procedure) occurs.

An intramuscular injection of acepromazine and hydromorphone is administered as a “premed”

*Sometimes a highly reactive and anxious patient requires an oral “pre-pre-medication” at home the night before and morning of with an anti-anxiety medication.

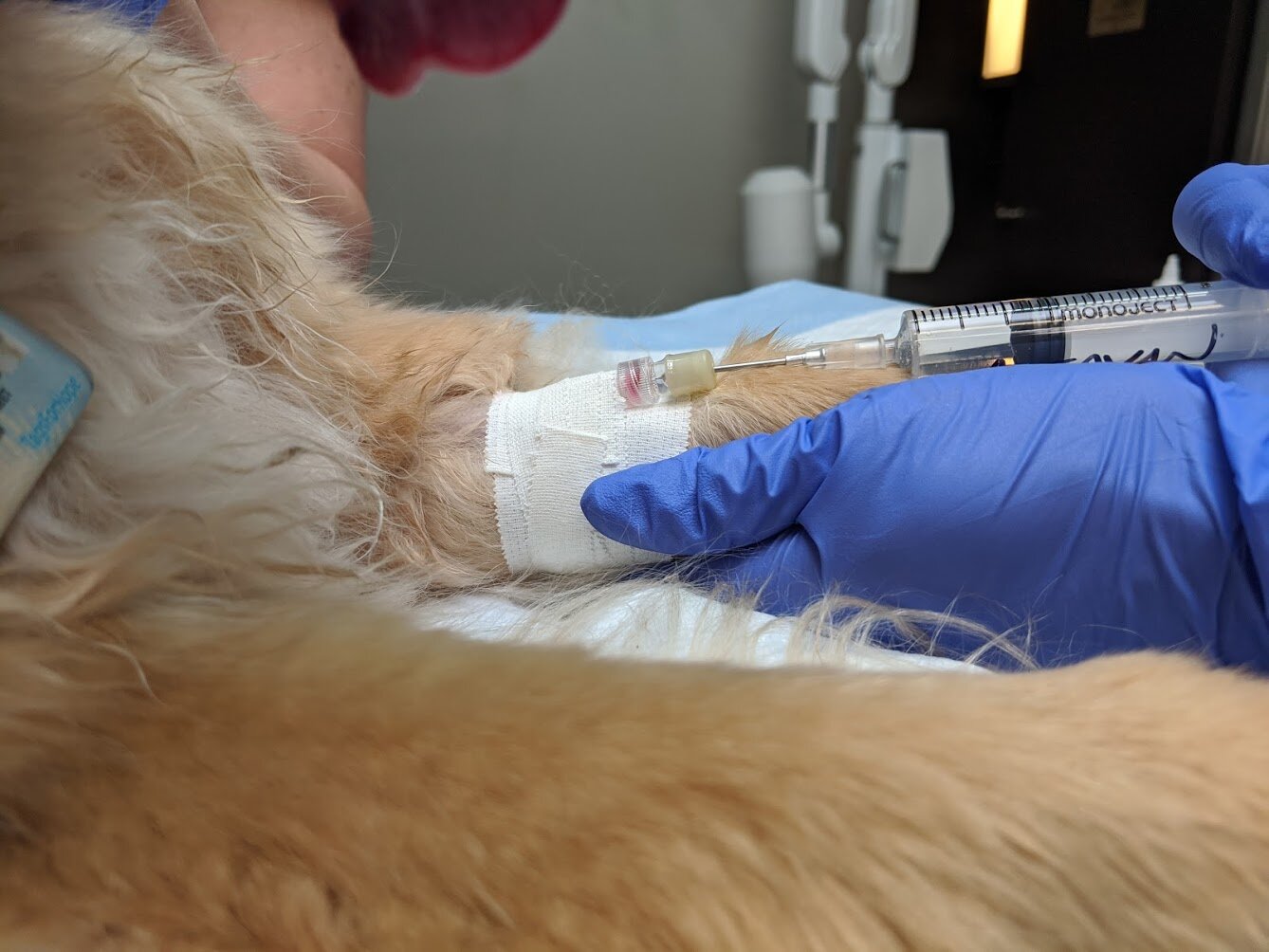

** Intravenous catheters are always placed to ensure venous access in the event that emergency drugs are needed, as well as to provide continuous intravenous fluids to maintain blood pressure.

An induction agent

2. Induction. This is an intravenous injection of a short-acting injectable anesthetic drug that allows for the smooth transition from an awake state to an anesthetized state. Once anesthetized, the patient is intubated with an endotracheal tube to achieve a secure airway. Oxygen flows continuously into the tube and patient for the duration of the anesthesia.

Intravenous injection of the induction agent

Intubation immediately following induction

3. Maintenance. An inhaled anesthetic flows (in addition to Oxygen) into the tube and patient at the lowest effective flow rate to create a steady state of anesthesia. The inhaled anesthetic is metabolized primarily in the lungs, allowing for a rapid recovery to an awake state once the anesthetic flow is stopped.

*All anesthetized patients are kept warm with specialized full body warming devices

Keeping our anesthetized patient warm with a forced-air warming unit

Side note: most anesthetic patients are required to fast for 12 hours before a general anesthesia. This practice is to reduce the risk of regurgitation and subsequent esophageal stricture.

MONITORING:

All general anesthesia (and to a lesser degree sedation) procedures are closely monitored and adjusted by trained veterinary personnel (in most cases a certified animal health technologist). Careful monitoring and adjusting of perioperative drugs (anesthetic agents, pain control and intravenous fluids) is imperative to ensure a safe and stable general anesthesia. In addition to patient monitoring of anesthetic depth, mucous membrane color, and respiratory rate, sophisticated monitoring machines are used to continuously measure:

1. Blood pressure

This monitor displays oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and temperature

2. Heart rate

3. Heart electrical activity/rhythm (ECG)

4. Oxygen saturation

5. Expired CO2 levels

6. Temperature

7. Intravenous fluid rate

RECOVERY:

Patient care and monitoring doesn’t end when the gas is turned off. The post-operative recovery period is a critical period of time where the most anesthetic deaths can occur. Pure Oxygen is administered once the gas anesthetic is turned off, and the patient’s vitals and anesthetic depth are closely monitored until it is ready for extubation. Once extubated, any breakthrough pain and disorientation is addressed as needed, and continual warmth provided. Intravenous catheters are left in place for several hours until the patient is up and alert. Some higher risk patients are kept on intravenous fluids for some time post-operatively.

When your veterinarian recommends a general anesthesia or sedation procedure, please know that this recommendation is not made lightly and that a lot of training, planning and careful consideration is involved. Each anesthesia is tailored to the individual patient’s unique temperament and health needs.

SOURCES:

Mathews et al. Factors associated with anesthetic-related death in dogs and cats in primary care veterinary hospitals. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. March 15, 2017, Vol. 250, No. 6, Pages 655-665. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.250.6.655